One morning I started my day thinking that I would try to find a little time to work on nodemon and woke up to a new pull request that fixed a small bug.

The only problem with the pull request was that it didn't have tests and didn't follow the contributing guidelines (which results in the automated deploy not actually running). The thread of replies didn't go too well...

MY EBOOK£5 for Working the Command Line

Gain command-line shortcuts and processing techniques, install new tools and diagnose problems, and fully customize your terminal for a better, more powerful workflow.

£5 to own it today

This post was originally published on A List Apart (in June 2016), and reprinted with the permission of A List Apart and the author, me.

About half way through the thread of replies, I started my usual descent into "what's the point, why do I bother, I should jack it all in", i.e. the self-destruct nature that I know isn't helpful to anyone. Though, thankfully, I held back.

The contributor was obviously extremely new to git and GitHub and just the small change was well out of their comfort zone, so when I then asked for the changes to adhere to the way the project works, it all kind of fell apart.

How do I change this? How do I make it easier and more welcoming for outside developers to contribute? How do I make sure contributors don't feel like they're being asked to do more than necessary?

This last point is important.

The real cost of a one line change

Many, many times in my own code, I've made a single line change, that could be a matter of a few characters and this alone fixes an issue. Except, that's never enough. In fact, there's usually a correlation between the maturity and/or age of the project and the amount of additional work to complete the change.

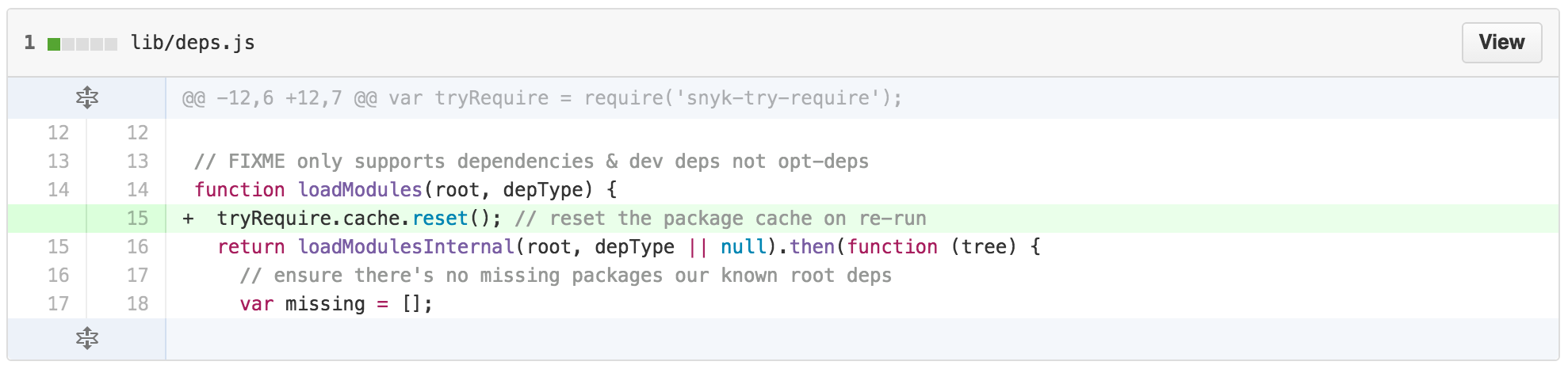

An issue in my Snyk work was fixed with this single line change:

In this particular example, I had solved the problem in my head very quickly, and realised that this was the fix. Except that I had to then write the test to support the change, not only to prove that it works, but more importantly, to prevent regression in the future.

Then once that change is in place, my projects all use semantic release to automate releases by commit message. And in this particular case, I had to then bump the dependencies in the project and then commit that with the right message format to ensure a release would inherit the fix.

All in all, the one line fix turned into: 1 line, 1 new test, tested across 4 versions of node, bump dependencies in a secondary project, ensure commit messages were right, and then wait for secondary project's tests to all pass before it was then automatically published.

TL;DR it's never just a one line fix.

Helping those first pull requests

Doing a pull request into another project can be pretty daunting. I'd say I've got a fair amount of experience and even I've started and aborted pull requests because I found the chain of events leading up to a complete PR too complex.

So how can I change my projects and GitHub repositories to be firstly, more welcoming to new contributors, but most importantly: how can I make that first PR easy and safe?

Issue and PR templates

Github recently announced support for issue and PR templates. These are a great start because now I can specifically ask for items to be checked off, or information to be filled out to help diagnose issues.

Here's what the PR template looks like for Snyk's CLI (I'm slowly adding these to all my repos):

- [ ] Ready for review

- [ ] Follows CONTRIBUTING rules

- [ ] Reviewed by @remy

#### What does this PR do?

#### Where should the reviewer start?

#### How should this be manually tested?

#### Any background context you want to provide?

#### What are the relevant tickets?

#### Screenshots

#### Additional questions

These items are not hard prerequisites on the actual PR, but it does encourage full information on the PR (this is partly based on QuickLeft's PR template).

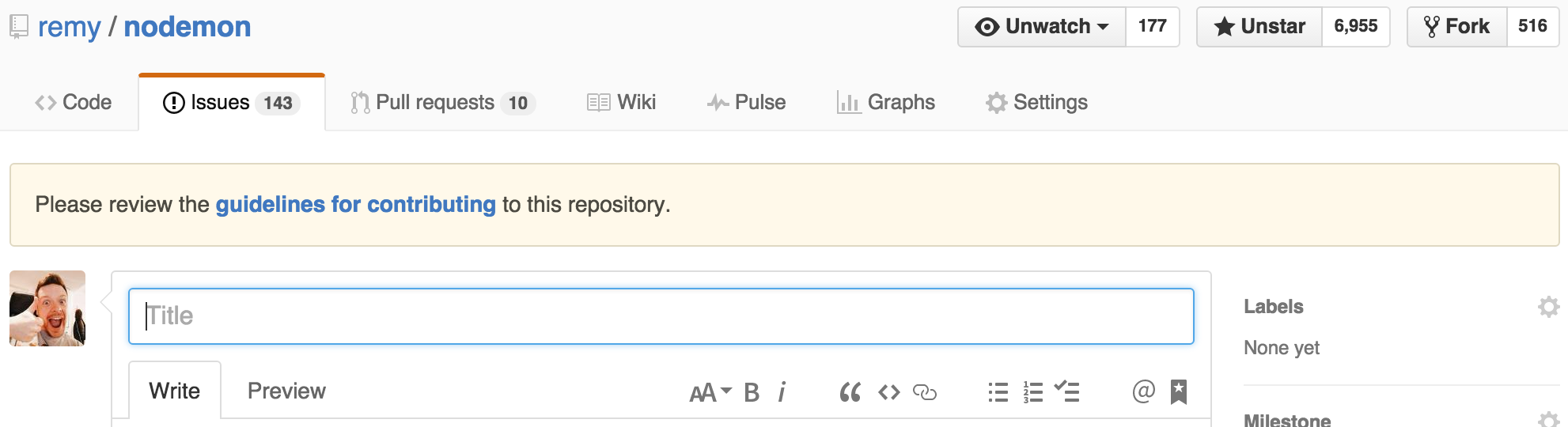

In addition, having a CONTRIBUTING.md file in the root of the repo (or in .github) means new issues and PRs include the notice in the header:

Automated checks

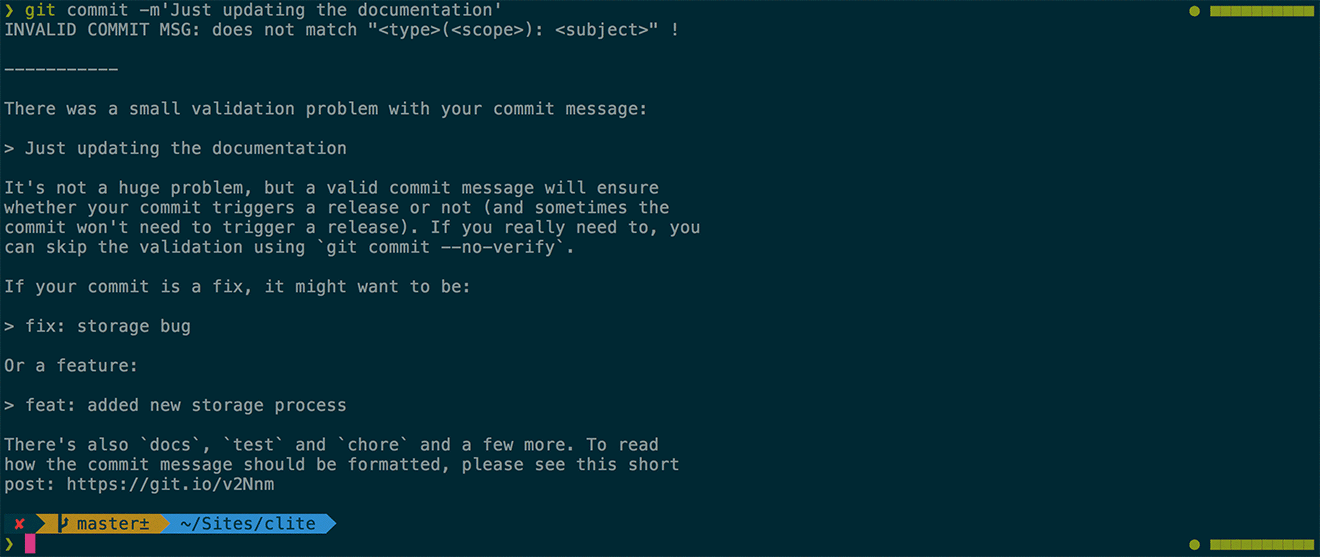

For context: semantic release will read the commits in a push to master, and if there's a feat: commit, it'll do a minor version bump. If there's a fix: it'll do a patch version bump. If the text BREAKING CHANGE: appears in the body of a commit, it'll do a major version bump.

I've been using semantic release in all of my projects, and so long as the commit message format is right, then there's no work involved in creating release, and importantly there's no work in deciding what the version is going to be.

Something that historically none of my repos had was the ability to validate contributed commits for formatting. In reality semantic release doesn't mind if you don't follow the commit format, but they're simply ignored and don't drive releases (to npm).

I've since come across ghooks that will run commands on git hooks, and in particular using a commit-msg hook that could run validate-commit-msg. The installation is relatively straight forward, but the reward back to the user is really good, because I say that the commit needs tweaking, can include examples and I can include links.

Here's what it looks like on the command line:

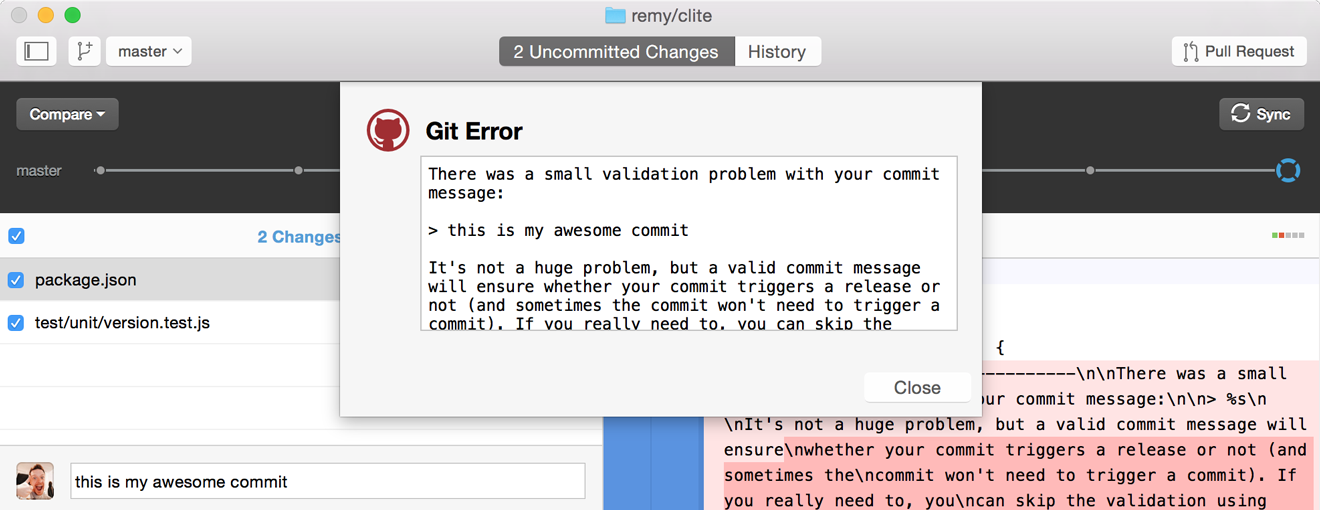

...and in the GitHub desktop app (for comparison):

This is work that I can load on myself to make contributing easier, which in turn, makes my job easier when it comes to managing and merging contributions into the project. In addition, for my projects, I'm also adding a pre-push hook that runs all the tests before the push to GitHub is allowed. That way it means if new code has broken the tests, the author is aware.

To see the changes required to get the output above, see this commit in my current tinker project.

Two further areas worth investigating are the commitizen project, and what I'd really like to see is a GitHub bot that could automatically comment on pull requests that say whether the commits are okay (and if not, direct the contributor on how to fix that problem) and also show how the PR would affect the release (i.e. whether it would trigger a release or not, whether a bug patch or a minor version change).

Including example tests

I think this might be the crux of problem: the lack of example tests in any project. Tests can be tricky because they consist of all kinds of minefields, including:

- knowledge of the test framework

- knowledge of the application code

- knowledge of testing methodology (unit tests, integration, something else)

- replicating test environment

Another project of mine, inliner has a disproportionately high success rate of PRs that include tests. I put that down to the ease in which users can add tests.

The contributing guide makes it clear that contributors don't even require that you even write test code. Authors just create a source HTML file and the expected output, and the test automatically includes the file and checks the output is as expected.

Adding specific examples of how to write tests, I believe, will make this barrier of entry easier. Perhaps linking to some sort of sample test in the contributing doc, or creating some kind of harness (like inliner does) to make it easy to add input and expected output.

Fixing common mistakes

Something I've also come to accept is that developers don't read contributing docs. It's okay, we're all busy, we don't always have time to pour over documentation. Heck, contributing to open source isn't easy.

I'm going to start including a short document on how to fix common problems in pull requests. Often it's amending a commit message or rebasing the commits. This is easy for me to document, and this way I can point new users to a walk through of how to fix their commits.

What's next?

In truth, most of these items are straight forward and not much work to implement. Sure, I wouldn't drop everything I'm doing and add them to all my projects at once, but certainly each active project that I'm working.

- Add issue and pull request templates

- Add ghooks and validate-commit-msg with standard language (most, if not all my projects are node based)

- Either make adding test super easy, or at least include sample tests (for unit testing and potentially integration testing)

- Add a contributing document that includes notes about commit format, tests and anything that can make the contributing process smoother

Finally, I (and we) always need to keep in mind that when someone has taken time out of their day to contribute code to my projects, whatever the state of the pull request. It's a big deal.

It takes commitment to contribute. Show some love for that.