Recreating the ZX Spectrum loader

Around the late 90s I bought mini digital camera, and digital camera prices were starting to be much more affordable to consumers.

I bought it from iwantoneofthose.com (so you might imagine the camera was much more of a gadget). The picture quality was fairly bad, even for that point in time, but one thing that struck me was that the camera would always (and slowly) autofocus and everything would be in focus. It was near impossible to create any sense of depth.

A depth of field, or so I think, creates so much more character to a picture and does a much better job of telling a story.

I thought it was funny, and even ironic, that cameras from 30 years previously would be manually focused and an automatically focusing camera would be a premium product. As time marched on technology improved and it saved the poor budding photographer from the pain of slightly out of focus pictures with a fully automated process.

Except now, manual, fine grain control, would be much harder to replicate in our more technologically advanced world.

I always thought it was funny and interesting that it's become hard to use new technology for old.

So this is precisely what this talk is about. Using new technology to replicate an old, reasonably useless, technology: replicating the ZX Spectrum tape loader audio and visuals (but without the tape).

What inspired this investigation and project, was the 2017 ffconf website design.

Each year, from the very first year back in 2009, the entire website design is rebranded and rebuilt from the ground up. This year, I had found a mobile app that could render my photos to look as though they had been rendered on retro computers, and the one particular filter that excited me was the ZX spectrum filter.

I began doing some draft design work (very draft since I'm no designer) around these photos and the small colour palette that the spectrum has (8 colours). The designer who went on to do the full design ran with my ZX spectrum theme and gave me an initial landing page that happened to have spectrum loading bars on the side. If you're not familiar with what theses are, I'll explain shortly.

Wouldn't it be great (in my usual developer ambitious naivety) to replicate this using JavaScript?

The ultimate goal would be: a user could drag and drop a file onto the page, you would hear and see the loading bar, and the page would progressively load the image. Just like the old days. Part of the problem I faced was that I don't really understand how audio works!

I was born in the 70s and enjoyed a childhood of the 80s. My family was privileged enough that we had computers in our home from an early point in time, and I remember various incarnations of the spectrum during my childhood.

The spectrum at the time seemed to be the most popular platform for games - 24,000 titles as of 2012 (although it was always intended for serious use), and boy did I play a lot of games!

The big prerequisite to playing all those games is the loading process. The loading process, certainly in my household, was this: put tape (that's like a super old usb stick that had turn dials inside them), in a tape player, adjust the volume, turn on the spectrum and type j "" which would get the spectrum ready to load. Then, hit play and wait for (what felt like) about 30 minutes, during which, the user must clasp their interlocked fingers together, rock back and forth and repeat (until game had loaded) "please load please load please load…".

This repeated preying to a computer over and over, was a common practice only because the success rate of a loading game was pretty much 50/50. And when it failed, it was frustrating as hell and you'd have to start the preying process all over again!

So when I started researching how the spectrum loader worked, I heard that loading sound again and it took me like a time machine back to the 80s.

This noise and visual junk actually provides an important function: both of these told me, the user, that a) the software was loading, b) that the loading was working.

It makes me think of all the times that I've loaded a page on a mobile device and I'm faced with a blank page. What happened? Did the data for the page fail to come over the wire? Did my mobile connectivity fail? Was there a JavaScript error? Does it just take a long time to load?

The 1982 ZX Spectrum had important user feedback that we sometimes fail at with today's amazing technology.

A laypersons understanding of the spectrum loader

It's great that technology has evolved so much beyond the Spectrum, and there are plenty of excellent emulators, even a number written in JavaScript that run in the browser. The thing about emulating old computers is, rarely, by which I mean never, have I seen the long loading times replicated. Although I suspect someone else has already done it, I was really left to try to understand all the inner workings and how to translate it to modern day JavaScript by myself.

There's some excellent resources on the web about this old technology, one main source being World of Spectrum which helped me breakdown what we're listening to when the tape loads:

- Pilot tone: this tells the loader that data is going to come (this has to be more than one second)

- Sync: this marks the end of the pilot tone and says that data is about to follow

- Datablock: this is the screechy noise that we hear. A single bit is comprised of two equal pulses, and typically the

1bit will be twice the length of a0bit

The pilot tone is, for me, the most memorable part of the loading process - because it would always start with this sound. It would also tell the spectrum that there was another block about to load (so it occurred more than once). So this is where I wanted to start.

Creating a pilot tone

With a little knowledge of the Web Audio API, I can create a single tone. To generate the tone, I'll use an oscillator node and set the frequency to my pilot tone frequency.

// create web audio api context

const audioCtx = new window.AudioContext();

// create Oscillator node

const oscillator = audioCtx.createOscillator();

// value in Hz, we'll change this

oscillator.frequency.value = 440;

// now connect it to the audio output

oscillator.connect(audioCtx.destination);

// now we hear the sound

oscillator.start();

This oscillator creates a tone that's 440Hz which is the "typical" instrument tuning note of an A note. Except this isn't the pilot tone frequency, and moving the value up and down really didn't help me find the actual frequency I wanted.

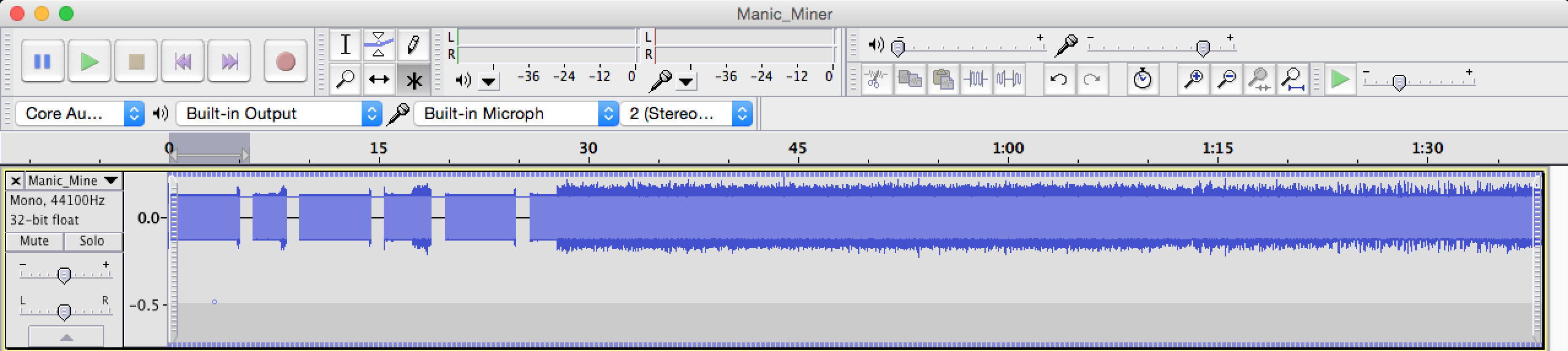

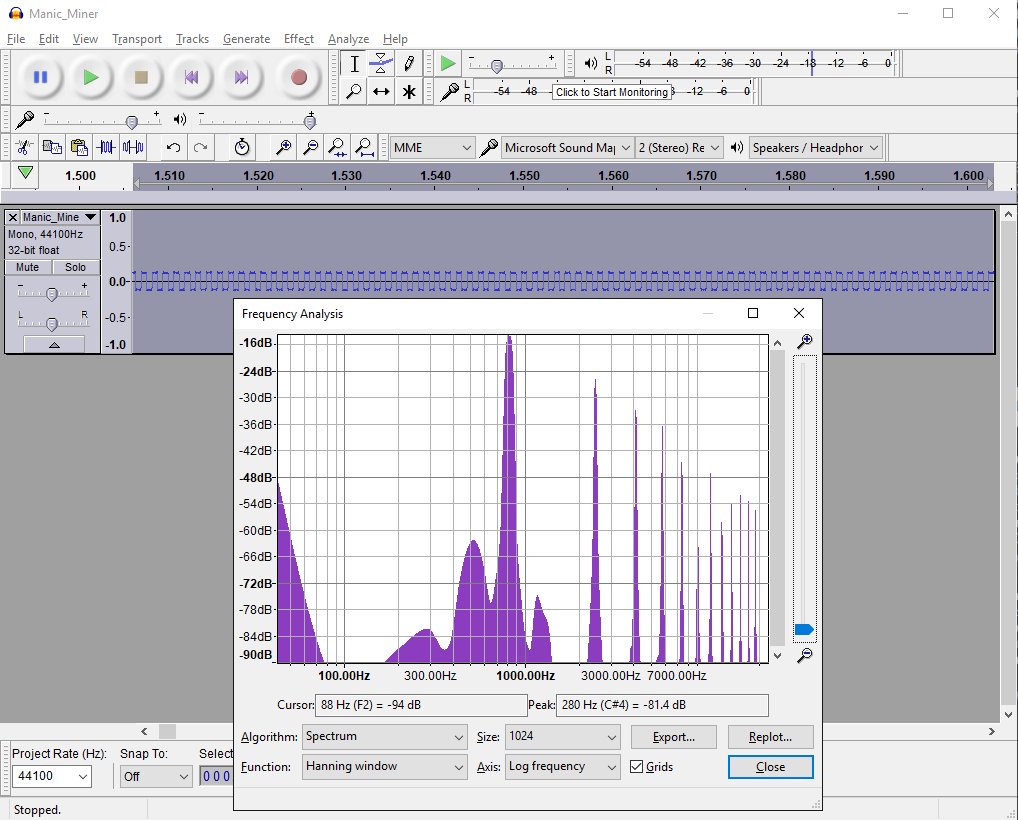

Using Audacity (that Patrick Lauke put me on to), we're able to see the pilot tone, and zoomed in, we can see that the tone is a square wave (not a sine wave, which is the default for an oscillatorNode) and then Patrick was able to identify that the tone was (about) 830Hz:

…which, when I change the code to play a square wave at 830Hz does actually sound about right:

// create web audio api context

const audioCtx = new window.AudioContext();

// create Oscillator node

const oscillator = audioCtx.createOscillator();

// square wave @ 830Hz

oscillator.type = 'square';

oscillator.frequency.value = 830;

// now connect it to the audio output

oscillator.connect(audioCtx.destination);

// now we hear the sound

oscillator.start();Note that the value isn't perfect, but we'll come onto this later on. That's the pilot tone, the next task was generate the sound for a series of 0s and 1s. But first, I need to actually get my binary from an image. So let's look at how that's done.

Collecting raw binary from images

This part is respectively straight forward. The image would be provided in two ways: a user would submit their own image, or we would use a stock image preloaded in the DOM.

If I'm using the reloaded image in the DOM, I'd first need to extract the blob data for the image which has to actually go via a canvas element:

async function renderImgToBlob(image) {

// 1. create a canvas and get the context

const canvas = document.createElement('canvas');

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

// 2. match the canvas height and width to the image

canvas.width = image.width;

canvas.height = image.height;

// 3. draw the image into to the canvas

ctx.drawImage(image, 0, 0);

// 4. return an async value of the blob of the canvas

return new Promise(resolve => {

canvas.toBlob(resolve);

});

}

Now with the blob, I take the File API and readBinaryAsString to construct a string of binary values:

const toBinary = s => s.charCodeAt(0).toString(2).padStart(8, '0');

const fileToBinary = async (blob) => new Promise(resolve => {

const reader = new FileReader();

reader.onloadend = () => {

const chars = reader.result.split('');

resolve({ binary: chars.map(toBinary) });

};

reader.readAsBinaryString(blob);

}

The result looks like this, and obviously very long as each byte is transformed into a string of 8 characters comprising of 0s and 1s:

10001001 01010000 01001110 01000111 …

Now that we've got the binary, we need to make a noise. And this is where my poor understand of audio gets tested!

Making a mess of sounds

At this point I really didn't know what I should do with the binary. I knew that I could generate white noise by populating an buffer with random values like the code below, but really I had no idea what the random values really related to:

// create web audio api context

const audioCtx = new window.AudioContext();

// create a 2 seconds buffer (more on this later)

const bufferSize = 2 * audioCtx.sampleRate;

const buffer = audioCtx.createBuffer(1, bufferSize, audioCtx.sampleRate);

const output = buffer.getChannelData(0);

// populate the buffer with random noise

for (let i = 0; i < bufferSize; i++) {

// random value from -1 to 1

output[i] = Math.random() * 2 - 1;

}

const whiteNoise = audioCtx.createBufferSource();

whiteNoise.buffer = buffer;

whiteNoise.start();

whiteNoise.connect(audioCtx.destination);The sound we hear is the binary being read from the tape in pulses.

Similarly to Pulse Width Modulation where a digital signal is used to create an analogue signal, the digital signal (of the speccy game) is put on to an analogue tape, so

A pulse is the important part. The pulse determines the sound we hear.

Importantly, it's the width of the sound, and not the level (amplitude) that determines the 0s and 1s.

The ZX spectrum CPU would run at 3.5Mhz, which means a single clock pulse is performed in 0.244ms. This is also known as a "T-state". A 1 bit is

But why?

Because I could. The web really is an amazing place. In the following talks you'll learn about the amazing technology that's right at our fingertips, and if you have an idea, however useful or not, browsers and the web have near unlimited resources.

Talking points

- New autofocus cameras being hard to replicate old techniques

- The spectrum loader

- What is it (generally)? ~4. Why is it important to me personally?~

- The sounds and breaking them down

- Starting simple: the pilot tone (855Hz square)

- Generating the binary for animate to render into sound

- Generating noise

- Generating junk noise - not really having an idea

- Pulse widths of

0s and1s ~11. Understanding a pulse's relation to a wave form~ - Maths, circles and sine waves and how they're related to sound

- Hertz and sample rates

- T-states, 3.5MHz clock speeds and binary

- Generating the right wave form

- Tape loading is actually a stream (scripting an audio node)

- Visualising using the analyser node

- Rotating bar examples into loading lines

- Optimising the paint during audio generation

- Bits, not bars - painting fake pixels

Drafts may be incomplete or entirely abandoned, so please forgive me. If you find an issue with a draft, or would like to see me write about something specifically, please try raising an issue.