What a packed week, what an honour and privilege to be part of, and what a superb job we did.

It's all live now: the project and all supporting materials online with all our original goals achieved 🎉

👉 https://worldwideweb.cern.ch

It's truly an honour to have been able to contribute to this tribute to history.

The final day

I'm a stickler for getting the job "done" - especially when it's a hackathon and the unit of work is distinct.

I know there would be bits I couldn't complete, but they would be de-prioritised and non-essential to bringing the feel of the 1990's browser back to life. So Friday was a day of laser focus!

However, the night before, around midnight, I had managed to make a fairly serious breakthrough in functionality and in that late night hacking session I'd managed to implement the ability to link between documents and update the author's markup to contain the correct link.

It might not sound like much, but those changes unlocked the ability to start save files (to IndexedDB), linking files and styling documents.

It was really nice to surprise the team with editable, saveable and linkable parts features (though at the same time I know there's occasions that it doesn't quite work - but isn't that the same with all demos 😱).

The final code will be made public via CERN's own Gitlab instance, probably on https://gitlab.cern.ch/nexus-project/nexus-browser

The hackathon ended with an impromptu demo of the simulation and feeling rather proud of the work we'd completed. Though secretly I also feel there's more I want to do (and even managed a few commits, fixes and features over this weekend).

It's almost funny that from Jean-François Groff's original list of upgrade proposals to the WorldWideWeb, our version pretty much feels like it's in the same state as when that document was written - i.e. a faithful replication of 1990! :)

Here's a short demo of navigation and page linking. Again, this is in a browser (fullscreen), using the mouse to do some navigation, and the keyboard for other (including "close all other windows" when I'm left with the summary window):

Supplementary content

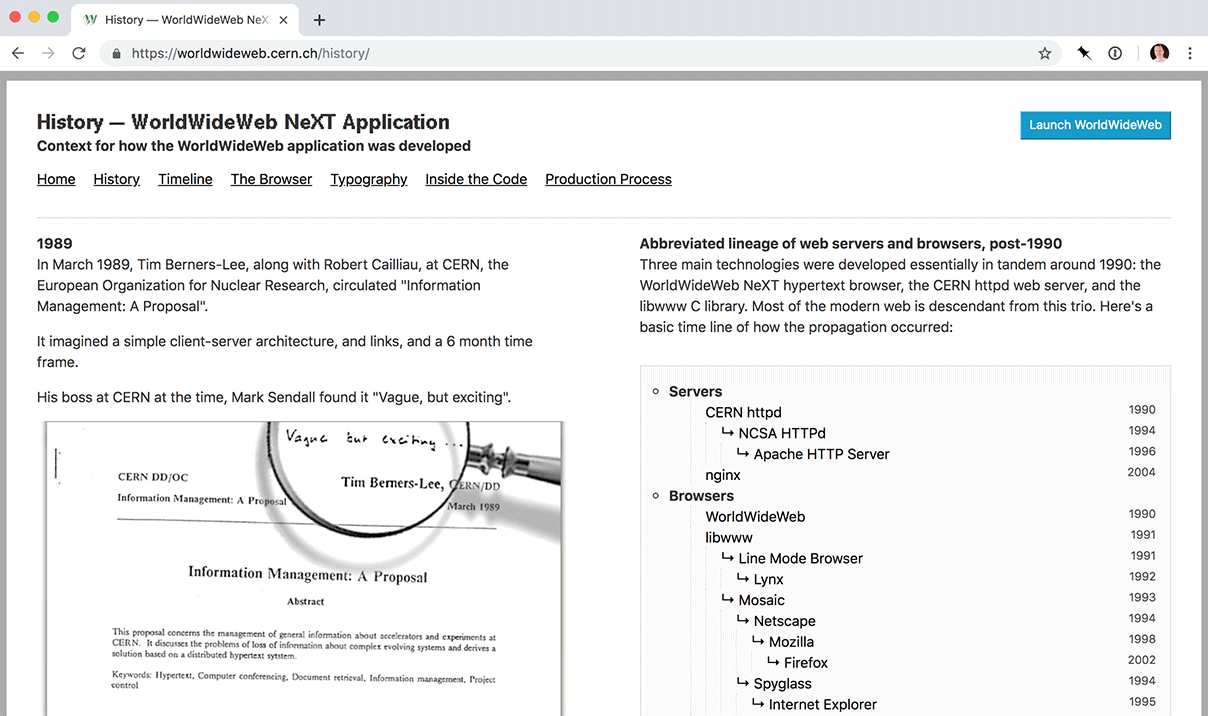

Whilst I was busy deep inside the code for the simulation, Craig Mod, Jeremy Keith, Kimberly Blessing and Martin Chiteri were busy completing the content web site that describes the history, documentation and the process the team took to complete the project.

The web site is quite superb and ful of great stories from how we got to have the world's first browser, one of my favourite parts being Kimberly's Inside the Code section.

Goals and fun insights

The aim of the project was to restore the world's first browser in a modern browser for the world to try out and experience.

The project would also document and include stories from the time that helped shape the technology we take for granted today.

For me, getting the details right in replicating the experience was important (in that we take pride in how we honour history).

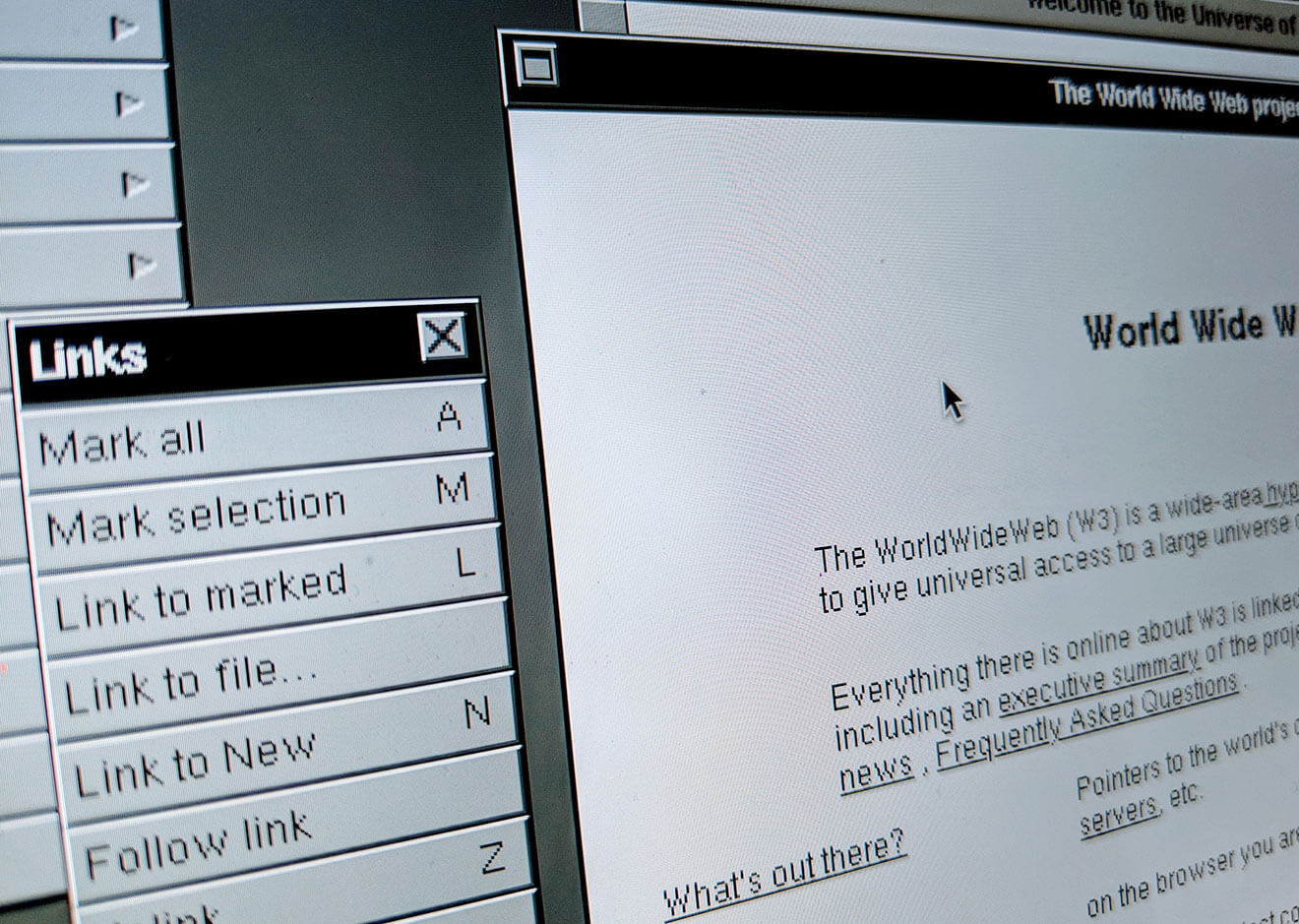

The WorldWideWeb browser came with some really interesting challenges, but it was also unique because not only could you browse the web (what there was of it in 1990…) but you could write for the web in the browser.

HTML editing and URLs weren't intended for the user. All the editing would be done in the rendered view. Styled directly in the browser (from a custom toolbar) and saved to networked drives (possibly pushed using FTP to other networks).

Without access to the source, linking was a key feature of the browser. In talking to Jean-Francois Groff he was able to enlighten me on what the <NEXTID 18> element was that we find so often on the very old pages on the web.

The NEXTID was key to making links work. The user would highlight and mark text they wanted to link to. This action would wrap the source text with a <A NAME=18> tag. The 18 being the value of the NEXTID and the tag would be incremented.

Of course, NEXTID was a tag never intended to have any contents. Modern browsers however, have always seen that tag and slurped the following text into a child node of NEXTID but it's supposed to be like a bodyless element akin to a LINK or META tag.

As I type this I now wonder if NEXTID came about entirely because of the WorldWideWeb browser's way of linking…

As for URLs, if you have a play with the simulation you might it rather tricky to spot the URL.

Then following links, due to the editable nature of the documents, meant that you need to double click on the links. A single click would of course set your cursor rather than follow the link as it would in today's browser.

(random, untreated picture to follow!)

Some hacks

In my work I used React to help with code organisation and state inside the software.

I also used Parcel to help me avoid getting bogged down in build configuration.

Of course these both provided me great affordances whilst on a few occasions causing me a headache because there was some bug, but I was so far away from "the metal", the actual executed JavaScript, it meant I had to work around issues

Although a large portion of the code is dedicated to the UI for the WorldWideWeb browser and also the NeXT operating system, the WebView - as we called the rendering logic - contains hacks that were only achievable using good old tried and tested DOM scripting.

To replicate the editable aspect of the page, I enabled contenteditable on the element that contains all the user HTML. Then using window.getSelection() I'm able to read the cursor position and manipulate the DOM modifying text nodes to reconstruct the link or styles the user selects from the UI.

Making jaggies

I kinda love jaggies. Part of replicating the feel was to get the low resolution effect we see on the NeXT operating system.

To do that, there was a number of different techniques employed:

- All images use

image-rendering: pixelated; - Font smoothing removed

font-smoothing: none - Custom hand drawn font

What's funny is that the original NeXT screen didn't have fully square pixels, whereas our screens have square pixels. Indeed, pixels are generally squared. For the font, Mark and Brian were working from a screenshot taken on the NeXT machine and transferred to their new machines.

What we noticed on the last day was looking closely at the NeXT monitor, we could see the pixels weren't quite square:

It's noticeable in the dot on the i character. Too late to do anything about it, and just one of those happy little stories inside the process of recreating such old technology for modern devices.

Still, the final result looks great:

The bits I missed

There's a lot of small bits here and there that there just wasn't time to implement. Let alone the fact that the reference version of WorldWideWeb was actually missing functionality too.

One great example was in the original WorldWideWeb browser has a (Diagnostic) menu under Document menu. At the bottom is Item, which on the WorldWideWeb browser had would completely shutdown the app in one unprompted abrupt exit. I wasn't too keen to implement a crashing browser!

There's also a lot of menu items, particularly around Edit menu that aren't implemented, but I've aimed to get the "main" features in.

I also suspect I'll sneak in a few commits to the project from home to make small tweaks here and there.

The whole of the Navigate menu functionality is missing, and it's one of my favourites from the original (so I definitely expect I'll have that deployed in the next week).

Time at CERN

It's strange to think I've been part of CERN on two occasions now. When I think of CERN, I think collider machines to explore the world of physics and the inception and creation of the web. Something that I wouldn't imagine myself being connected too, I simply see these people as über smarties.

The first time I arrived at CERN in 2013, I didn't really appreciate the gravity of the importance of where I was. It was a hacking job, something I'm well suited to, and there was a vague idea that it was a cool place to work from.

This time around I was fully prepared to enjoy and appreciate my surroundings (whilst also hacking).

The cafeteria at CERN in a central hub for people. We chatted with Robert Cailliau as he recounted his early memories over lunch.

We spent time hanging out and quizzing Jean-Francois Groff both at our working space, but also in the cafeteria.

We heard how he and Tim Berners-Lee discussed the names of the WorldWideWeb browser, words that are common lingo to us today.

How physicists how first used the colliders when CERN came to be in 1957, can still be picking up lunch in those same cafeterias.

Along with that, it's very clear that CERN is a collaborative and welcoming place for hacking science.

We also got to meet some of the students that were placed at CERN. Bright and inquisitive, and not even 16. The place seems to bring the best out in people - or certainly that's what I had seen in my two short visits.

It really was something that I'm very proud of being part of, and I wanted to thank my team mates:

- John Allsop (Australia)

- Kimberly Blessing (USA)

- Mark Boulton (U.K.)

- Martin Chiteri (Canada / Kenya)

- Jeremy Keith (U.K. / Ireland)

- Craig Mod (Japan / USA)

- Angela Ricci (France / Brazil)

- Brian Suda (Iceland / USA)

And James Gillies for initiating the project and opening the invitation, and the supporting Web Team at CERN, including Kostas, Sebastian, Edwardo and Sotirios.

Then it was off for dinner at the airport to fly home and arrive safe and sound in my own bed at 1am on Saturday morning 💤