I gave this talk: I know jQuery. What now? at jQuery UK 2013 (video of the talk), but instead of my usual approach of post-it explosion on my desk, I wrote a post first, and created the slides from the post. So here is my (fairly unedited) quasi-ramble on how I used jQuery, and how I'm looking at where I'm using native browser technology.

Addition resources

As this post was also the content for a talk I've given, I've added addition resources as they've been published below:

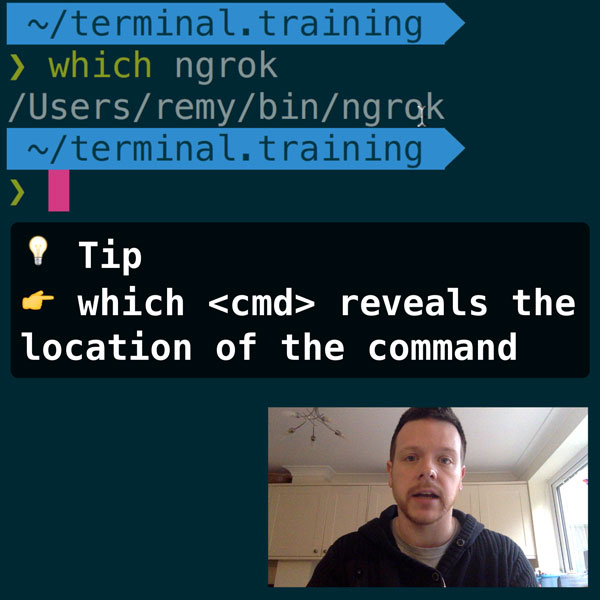

READER DISCOUNTSave $50 on terminal.training

I've published 38 videos for new developers, designers, UX, UI, product owners and anyone who needs to conquer the command line today.

$49 - only from this link

7 years ago...

17-Jun 2006, I publish my first (ever) real blog post: taking regular JavaScript and simplifying to jQuery syntax. It turned 14 lines of JavaScript in to 3 lines of jQuery (pre jQuery 1.0).

Most importantly, it went from some fiddly DOM navigation to a simple CSS expression, and added a class once done. The original JavaScript was also quite brittle, so it meant you either had the same markup.

I introduced jQuery to the team of developers I worked with back in mid-2000s and even the designers could see the appeal (since they generally understood CSS selectors (and hence how jQuery for Designers was born)).

DOM navigating was suddenly easy

Back then the DOM was hard to navigate. You could be sure that if it worked in Firefox 1.5, it wouldn't work in IE6.

The ease in which jQuery could be learnt was the appeal to me. All the DOM navigation was done using CSS expression using some insane black box magic that John Resig had come up - saving my limited brain power, and once I had those DOM nodes, I could do what I wanted to them (usually some combinations of showing, hiding, fading and so on).

Groking ajax

jQuery also abstracted ajax for me. The term had only just been coined earlier in 2005, but documentation was not wide, nor trivial to understand (remember the lower power computing power of my brain).

It was the first time I really had to deal with the XMLHttpRequest object, and when seeing it for the first time, understanding the onreadystatechange event and the combination of this.status and this.readyState wasn't overtly clear! jQuery (and other libraries) also tucked away the mess that was XHR in IE via ActiveX...

function getXmlHttpRequest() {

var xhr;

if (window.XMLHttpRequest) {

xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

} else {

try {

xhr = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP");

} catch (e) {

try {

xhr = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP");

} catch (e) {

xhr = false;

}

}

}

return xhr;

}

// disclaimer: John's jQuery version is a lot more elegant!

Once I could see that using the ajax utility inside of jQuery to suck in a URL's HTML (which was typically the way we wanted to do ajax), then ajax suddenly clicked.

jQuery quickly became my standard utility for many years. It was my Swiss Army Knife, as it were, to steal Adam's talk title!

Back to the future: today

Let's fast forward back to today. What's happened over those years?

For starters, my default starting position is no longer "include jQuery by default". I understand more JavaScript and how things work.

I have my own criteria for when to include jQuery, and when not to include jQuery. But if I don't include jQuery, then what?

In those 7 years, quite a bit has happened. Probably one of the most important steps forward was the introduction of querySelectorAll.

Being able to give a native function of a browser a CSS expression, and it doing the work to navigate the DOM is a huge (literally) part of jQuery. Basic support was in Chrome from the outset, and in IE8 and Firefox 3.5 around mid-2009.

Andrew Lunny (of PhoneGap & Adobe) has the brilliant simplicity on the bling function:

var $ = document.querySelectorAll.bind(document);

Element.prototype.on = Element.prototype.addEventListener;

$('#somelink')[0].on('touchstart', handleTouch);

Beautifully simple.

I've taken this idea a little further and used it on a few specific projects, adding support for chaining, looping and simplifying the syntax. Comes in at <200 bytes gzipped. But the point is that today we have features natively available, and I'm trying to consider my audience before dropping in jQuery by default.

When I always use jQuery

Before I look at how I can go without jQuery, naked, let me just share when I drop jQuery in to a project. There's usually a few of very specific criteria that either has me start with jQuery or switch from a bespoke solution in favour of jQuery.

Before I do, I should point out when I absolutely don't use jQuery: If I'm trying to replicate a browser bug, I never use a library. If you're trying to corner a bug, so that you can file an issue, you want your case as minimal as possible (unless of course you're filing a bug on jQuery!).

1. When the project has to work in non-cutting-mustard browsers

The BBC have been quite vocal in what they define as "cutting the mustard", and now I think about it, that's my benchmark for when to include jQuery by default.

If I know I have to work with browsers that don't cut the mustard, and they're part of the core audience, then I'll start with jQuery in my initial code.

What is cutting the mustard?

It's almost as simple as: does this browser have querySelectorAll?

The BBC use the following test for cutting the mustard:

if ('querySelector' in document &&

'localStorage' in window &&

'addEventListener' in window) {

// bootstrap the JavaScript application

}

I know off the top of my head IE8 doesn't support addEventListener (but there is a polyfill), so if that's an important browser to the project, then I know that I don't want to start the project hoop jumping for IE8.

This isn't to say those projects that I start without jQuery won't support IE8, it's more that you want to start simple, and keep development simple from the outset. If I start a project with a bag of hacks - I know it's going to be a hassle.

I also class this as "when complexity outweighs ease".

2. When it's quick and dirty

If I'm creating a proof of concept, testing an idea out, and generally hacking and creating a JS Bin, I'm usually adding jQuery by default. It saves me thinking.

jQuery-free

You might be thinking "so, does Remy use jQuery, and if he doesn't then does he just re-implement it all?".

I certainly don't want to re-invent the wheel. If I find that developing without jQuery only leads me to re-creating a lot of jQuery's functionality from scratch, then I'm clearly wasting my own time.

No, there's a lot of patterns where I will build my application code without a library and rely on native browser technology to do the job. And if there's a small part of that functionality missing, I might turn to polyfills - but only after careful review that it makes sense.

So how do I live without jQuery, and how good is the support?

document.ready

Even when I use jQuery, if I (or my company) have control of the project, I very, very rarely use document.ready (or the shortened version $(function)).

This is because I put all my JavaScript below my DOM, before the </body> tag. This way I always know the DOM is going to be compiled by this point.

Hopefully it's common knowledge by now, but JavaScript blocks rendering. Put your JavaScript above the content, and your server stalls, and you get a blank page. I've used this example many times before, but twitter's "badge" (a long time ago) used to be put inline to your HTML. Their site would often go down, and as my blog (also carrying the twitter badge) would hang with a blank page - giving the appearance that my site was down.

.attr('value') and .attr('href')

It makes me sad when I see jQuery to retrieve a value from an input element:

$('input').on('change', function () {

var value = $(this).attr('value');

alert('The new value is' + value);

});

Why? Because you can get to the value using this.value. More importantly - you should think about how you're using a JavaScript library. Don't unnecessarily invoke jQuery if you don't need to.

In fact, this isn't a jQuery thing - it's a best practise thing. The code should simply read:

$('input').on('change', function () {

alert('The new value is' + this.value);

});

It's also common to use jQuery to get the href of an anchor: $(this).attr('href'), but you can also easily get this from knowing the DOM: this.href. However, note that this.href is different, it's the absolute url, as we're talking about the DOM API, and not the element. If you want the attribute value (as it's suggested in the jQuery version), you want this.getAttribute('href').

Then there's setting the class on an element, you don't need jQuery for that either if you're just adding a class.

I've seen this before:

<script src="http://code.jquery.com/jquery.min.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<script>

$('body').addClass('hasJS');

</script>

But why not:

</head>

<body>

<script>

document.body.className = 'hasJS';

</script>

Probably the most important change in the version below, is there's no jQuery being included first just to set a class name on the body to determine whether JavaScript is available.

If the body might have a class already, just append (jQuery has to read the className property too): document.body.className += ' hasJS'.

And this is where we start to run in to issues with class names and tracking what classes they have and don't have. But browsers have this functionality natively too.

classList for add, remove & toggle

HTML5's classList support is in all the latest production browsers (note not in IE9 - but this is a case where I might choose to polyfill).

Instead of:

$('body').addClass('hasJS');

// or

document.body.className += ' hasJS';

We can do:

document.body.classList.add('hasJS');

Isn't that pretty?

What about removing:

$('body').removeClass('hasJS');

// or some crazy-ass regular expression

Or we can do:

document.body.classList.remove('hasJS');

But more impressive is the native toggle support:

document.body.classList.toggle('hasJS');

// and

document.body.classList.contains('hasJS');

To set multiple classes, you add more arguments:

document.body.classList.add('hasJS', 'ready');

What does suck though, is the weird issues - like don't use a empty string:

document.body.classList.contains('');

// SyntaxError: DOM Exception 12

That's pretty rubbish. But! On the upside, I know the problem areas and I avoid them. Pretty much what we've grown up on working with browsers anyway.

Storing data

jQuery implemented arbitrary data storage against elements in 1.2.3 and then object storing in 1.4 - so a little while ago.

HTML5 has native data storage against elements, but there's a fundamental difference between jQuery and native support: object storage won't work in HTML5 dataset.

But if you're storing strings or JSON, then native support is perfect:

element.dataset.user = JSON.stringify(user);

element.dataset.score = score;

Support is good, but sadly no native support in IE10 (though you can add a polyfill and it'll work perfectly again - but that's a consideration when using dataset).

Ajax

Like I said before, jQuery helped me grok ajax fully. But now ajax is pretty easy. Sure, I don't have all the extra options, but more often than not, I'm doing an XHR GET or POST using JSON.

function request(type, url, opts, callback) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest(),

fd;

if (typeof opts === 'function') {

callback = opts;

opts = null;

}

xhr.open(type, url);

if (type === 'POST' && opts) {

fd = new FormData();

for (var key in opts) {

fd.append(key, JSON.stringify(opts[key]));

}

}

xhr.onload = function () {

callback(JSON.parse(xhr.response));

};

xhr.send(opts ? fd : null);

}

var get = request.bind(this, 'GET');

var post = request.bind(this, 'POST');

It's short and simple. XHR is not hard and it's well documented nowadays. But more importantly, having an understanding of how it really works and what XHR can do, gives us more.

What about progress events? What about upload progress events? What about posting upstream as an ArrayBuffer? What about CORS and the xml-requested-with header?

You'll need direct access to the XHR object for this (I know you can get this from jQuery), but you should get familiar with the XHR object and it's capabilities, because things like file uploads via drag and drop is insanely easy with native functionality today.

Finally forms!

The jQuery form validation plugin was a stable plugin from the early days of jQuery, and frankly made working with forms so much easier.

But regardless of your client side validation - you must always run server side validation - this remains true regardless of how you validate.

But what if you could throw away lines and lines of JavaScript and plugins to validate an email address like this:

<input type="email">

Want to make it a required field?

<input type="email" required>

Want to allow only specific characters for a user?

<input pattern="[a-z0-9]">

Bosh. It even comes with assistive technology support - i.e. the keyboard will adapt to suit email address characters.

Since these types fall back to text, and you have to have server side validation, I highly encourage you to rip out all your JavaScript validation and swap in native HTML5 form validation.

jQuery animations VS. CSS animations VS. JavaScript animations

It's not really a contest. CSS wins. Animating using CSS is being processed on the GPU. Animating in JavaScript has the additional layer of computation in the simple fact there's JavaScript.

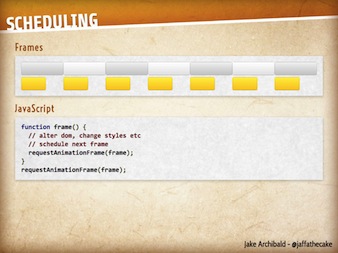

Even then, if I'm writing the code myself, I'm going to choose to use requestAnimationFrame over setInterval based animations.

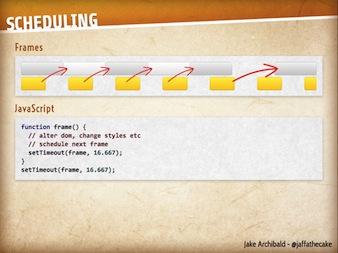

Jake Archibald has some excellent slides showing the issue here, whereby setInterval won't be smooth and will quickly start to drop frames:

What's more, CSS animations go through the same scheduler as requestAnimationFrame, which is what we want to use.

So if your browser support allows for it, use CSS animations. Sure, it's not as easy as $foo.animate('slow', { x: '+=10px' }) but it's going to be cleaner and smoother. It should be a well known fact that touching the DOM is expensive. So if you're animating the x position of an element by updating the el.style.left attribute, you're going back and forth for the animation.

However, if you can simply do foo.classList.add('animate'), the CSS class animate will transition the left position of the element. And you have control if that's just the left property, or if you take advantage of hardware acceleration by using translateX with translateZ(0).

But what about my animation end callback I hear you all cry?! That's available too. Though it's a little icky:

el.addEventListener("webkitTransitionEnd", transitionEnded);

el.addEventListener("transitionend", transitionEnded);

Note the the lowercase 'e' on 'end'...

A few kind people on twitter did also point me to a sort-of-polyfill for jQuery, that enhances the .animate function if CSS animations are available.

There's also a separate plugin called Transit which gives you JavaScript based control over creating CSS animations. A really nice aspect (for me) is the chaining support. Since it relies exclusively on CSS animations, it requires IE10 and above.

Which begs me to ask: why does this plugin require jQuery specifically?

Aside: jQuery plugins - just because.

Me:

I don't know why, but I really want to hurt the people who write jQuery plugins that don't really need jQuery. /seeks-anger-management

@rem Me too, I suspect there's a support group for that. Probably rather large.

I was working on a project recently, and knew of the fitText.js project. I went to drop it in, but then spotted that it needed jQuery.

Hmm. Why?

It uses the following jQuery methods:

.extend.each.width.css.on(and not with much thought to performance)

The plugin is this:

$.fn.fitText = function( kompressor, options ) {

// Setup options

var compressor = kompressor || 1,

settings = $.extend({

'minFontSize' : Number.NEGATIVE_INFINITY,

'maxFontSize' : Number.POSITIVE_INFINITY

}, options);

return this.each(function(){

// Store the object

var $this = $(this);

// Resizer() resizes items based on the object width divided by the compressor * 10

var resizer = function () {

$this.css('font-size', Math.max(Math.min($this.width() / (compressor*10), parseFloat(settings.maxFontSize)), parseFloat(settings.minFontSize)));

};

// Call once to set.

resizer();

// Call on resize. Opera debounces their resize by default.

$(window).on('resize orientationchange', resizer);

});

};

.extend is being used against an object that only has two options, so I would rewrite to read:

if (options === undefined) options = {};

if (options.minFontSize === undefined) options.minFontSize = Number.NEGATIVE_INFINITY;

if (options.maxFontSize === undefined) options.maxFontSize = Number.POSITIVE_INFINITY;

return this.each used to loop over the nodes. Let's assume we want this code to work stand alone, then our fitText function would receive the list of nodes (since we wouldn't be chaining):

var length = nodes.length,

i = 0;

// would like to use [].forEach.call, but no IE8 support

for (; i < length; i++) {

(function (node) {

// where we used `this`, we now use `node`

// ...

})(nodes[i]);

}

$this.width() gets the width of the container for the resizing of the text. So we need to get the computed styles and grab the width:

// Resizer() resizes items based on the object width divided by the compressor * 10

var resizer = function () {

var width = node.clientWidth;

// ...

};

It's really important to note that swapping .width() for .clientWidth will not work in all plugins. It just happen to be the right swap for this particular problem that I was solving (which repeats my point: use the right tool for the job).

$this.css is used as a setter, so that's just a case of setting the style:

node.style.fontSize = Math.max(...);

$(window).on('resize', resizer) is a case of attaching the event handler (note that you'd want addEvent too for IE8 support):

window.addEventListener('resize', resizer, false);

In fact, I'd go further and store the resizers in an array, and on resize, loop through the array executing the resizer functions.

Sure, it's a little more work, but it would also easy to upgrade this change to patch in jQuery plugin support as an upgrade, rather than making it a prerequisite.

Rant will be soon over: it also irks me when I see a polyfill requires jQuery - but I know the counter argument to that is that jQuery has extremely high penetration so it's possibly able to justify the dependency.

Closing

My aim was to show you that whilst jQuery has giving me such as huge helping hand over the years (particularly those years of poor interoperability), that native browser support is a long way to doing a lot of the common workflows I have when writing JavaScript to "do stuff" to the DOM.

Forget about X feature doesn't work in Y browser - approach it from the point of view of: what am I trying to solve? What's the best tool for the job? What's my audience?

I still believe in progressive enhancement, but I don't believe in bending over backwards to support an imaginary user base (because we don't have data to say what browsers our users are using).

Google (last I read) support latest minus 1. I try to start from the same baseline support too.

I'll continue to use jQuery the way that suits me, and I'll continue to evangelise that front end devs learn what the browsers they work with are capable of.

With that then, I close, and I hope this has been helpful to you.

Maybe some of you knew all this already (though I would question why you're attending/reading this!), hopefully I've shown some of you that there's a world beyond jQuery and that you can start using it today in some of your projects.

Maybe some of you are new to jQuery - I hope that you go on to look further in to what JavaScript and the DOM are capable of.

But for the majority of you: I'm singing to the choir. You're already invested. You already believe in standards, doing it right, learning and bettering yourself. It's those people who aren't getting this information that you need to help.

You need to share your experiences with the others around you. You're the expert now, and it's up to you to help those around you, to help them come up to your standards and beyond.

Conferences will be looking for new speakers, new experts: you are that person.